The story of America’s rise from thirteen scattered colonies to a union of fifty sovereign states is far more than a chronological recounting of events—it is a tapestry of courage, conflict, divine timing, and a relentless pursuit of liberty that forged a new kind of civilization on Earth. At its core, this transformation was not simply political; it was spiritual, cultural, and philosophical. It was a grand experiment in human freedom, unlike anything the world had ever seen, and one whose ripples continue to shape the global landscape. To understand how the Republic expanded across a continent and stood firm through wars, internal crises, and generational change, one must begin with the earliest seeds of resistance and vision planted during America’s colonial era.

In the early eighteenth century, the thirteen colonies existed as fragmented satellites of the British Crown—economically exploited, politically constrained, and culturally divided by geography, religion, and regional interests. Yet beneath this fragmentation lived a growing sense of identity. Colonists who had braved storms, wilderness, famine, and the unknown had developed a rugged independence and a deep conviction that human beings were meant to stand upright, not kneel under the weight of tyranny. This internal understanding—this whisper of sovereignty—began spreading like a slow-moving fire. It rose in the taverns of Boston, the farms of Pennsylvania, the plantations of Virginia, and the small coastal towns that dotted the Atlantic shoreline. Though Britain attempted to suppress it through taxation, military presence, and legal control, the human spirit responded instinctively: the more it was pressed, the stronger it grew.

The American Revolution, often reduced to muskets and battlefields, was actually the culmination of decades of philosophical resistance. Figures like Samuel Adams, James Otis, Patrick Henry, Benjamin Franklin, and Thomas Jefferson articulated what people already felt in their bones: that freedom was not granted by rulers, but endowed by the Creator. This belief was revolutionary, radical, and dangerous. It challenged the entire architecture of monarchy, empire, and centralized control. But it resonated deeply with farmers, merchants, craftsmen, ministers, and ordinary men and women who had tasted the hardships of frontier life and refused to surrender their autonomy to a distant king.

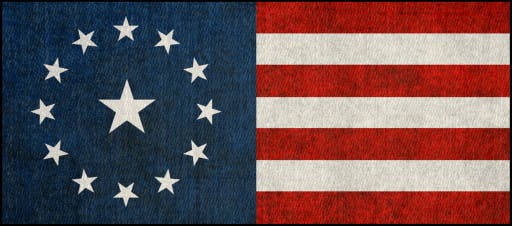

When the Declaration of Independence was signed in 1776, it was not merely an act of political rebellion; it was a metaphysical declaration—a recognition of natural law and divine sovereignty over human institutions. It crystallized the idea that government derives power from the consent of the governed. This single principle would eventually become the cornerstone of American expansion, informing everything from the Bill of Rights to the admission of every future state in the Union.

The early years of independence were turbulent and uncertain. The Articles of Confederation created a weak central government, unable to levy taxes or enforce national unity. States quarreled, economies faltered, and outside threats loomed. Yet this period of chaos served a vital purpose: it revealed the necessity of a stronger but still limited constitutional structure. The Constitutional Convention of 1787 became the turning point at which the Founders forged a new blueprint—one balancing federal strength with state sovereignty, unity with autonomy, and liberty with order. This framework became the vessel through which the fledgling nation could grow.

As the United States stabilized under the Constitution, the vision of expansion began to take shape. The Founders understood that America’s destiny stretched far beyond the original thirteen colonies. The Northwest Ordinance set the precedent: new territories would not be mere appendages, but fully sovereign states equal to the original ones. This principle—the equality of states—ensured that expansion would be grounded in law, not conquest or hierarchy. It would become one of America’s most important structural harmonies.

The Louisiana Purchase in 1803 doubled the size of the nation overnight, opening vast unexplored lands. Whether viewed as geopolitical brilliance or divine providence, the acquisition provided space for new states like Louisiana, Arkansas, Missouri, Iowa, Kansas, Nebraska, and the Dakotas. Each was admitted through constitutional processes, strengthening the Union and fulfilling the Founders’ vision of a continental Republic.

Yet expansion was not without conflict. The tension between free and slave states threatened to fracture the nation. Compromises like the Missouri Compromise and the Compromise of 1850 temporarily stabilized the Union, but the deep moral and constitutional crisis of slavery pushed the Republic to the brink. The Civil War, though devastating, ultimately reaffirmed the indivisible nature of the Union and re-anchored the nation to its foundational principles. The Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments expanded the definition of sovereignty and individual rights, ensuring that the Republic endured—not merely as a collection of states, but as a unified force anchored to liberty.

Following Reconstruction, a wave of western expansion propelled the nation toward its modern shape. States like Colorado, Montana, Washington, Idaho, Wyoming, Utah, and the plains states entered the Union. Each one brought new resources, cultures, and strategic value. Alaska and Hawaii—admitted in 1959—represented the final stage of America’s geographical evolution, expanding its sovereignty beyond the continental frontier and anchoring it in the Pacific and the Arctic.

But the journey from thirteen to fifty was also marked by unseen forces—cycles of renewal, periods of providential opportunity, and moments of crisis that required courage, unity, and vision. Time and again, America stood at crossroads where the decisions of leaders and Americans shaped the destiny of generations. Whether resisting tyranny, rebuilding after war, confronting internal injustice, or expanding the frontiers of innovation, the drive toward sovereignty remained the central thread.

Today, as America stands as a fifty-state Republic, the deeper truth emerges: the nation’s expansion was not accidental. It was the manifestation of an underlying frequency—a collective desire for freedom, self-governance, and the pursuit of higher principles. This journey mirrors the evolution of consciousness itself: growth through struggle, awakening through challenge, and alignment through clarity. The transformation from thirteen colonies into fifty sovereign states reflects not just territorial growth, but the expansion of a national identity rooted in natural rights, constitutional law, and the enduring impulse toward liberty.

In this light, the birth of the nation becomes more than a historical narrative—it becomes a living testament to the human spirit’s capacity to rise, expand, and align with timeless principles. The Republic did not simply grow; it unfolded, layer by layer, into its destined form. And as the nation continues its journey into a new era of awakening, the foundation laid by those early colonies—those thirteen seeds of sovereignty—remains the anchor and the compass guiding America into its next phase of evolution.