The concept of sovereignty—perhaps the most powerful and misunderstood principle in the entire American framework—sits at the heart of the Republic. The Founders did not create the united States of America as a nation where power trickles downward from a central authority; they created a system where authority flows upward from the individual and outward through sovereign states. By design, the individual is the primary unit of power, the states are the guardians of regional authority, and the federal government is the smallest, most limited entity—the servant of all, not the master of any. Understanding this structure is essential to reclaiming the true meaning of liberty, and to recognizing how far modern governance has drifted from the original constitutional blueprint.

Sovereignty begins with the individual. In the American model, the individual is recognized as a free and self-governing being endowed by the Creator with inherent rights—rights that preexist government and cannot be revoked by legislative decree. This belief, woven into the Declaration of Independence and manifested throughout the Constitution and Bill of Rights, establishes the individual as a sovereign entity. A sovereign individual is not a subject; they are not property; they are not a corporate asset to be managed, indexed, or controlled. They stand above the state in authority and equal to all others in dignity, responsibility, and natural law.

To fully understand individual sovereignty, one must appreciate the distinction between natural rights and civil privileges. Natural rights arise from existence itself—speech, self-defense, conscience, movement, property, privacy, and the pursuit of one’s purpose. Civil privileges are those created by governments—licenses, permits, registrations, classifications, and benefits. The Founders made clear which one forms the foundation of the Republic: natural rights. Civil privileges may be granted or withheld, but natural rights cannot be surrendered unless through ignorance or coercion. When individuals forget this distinction, they begin to treat privileges as rights and rights as negotiable, inadvertently handing their sovereignty to institutions that were never meant to possess it.

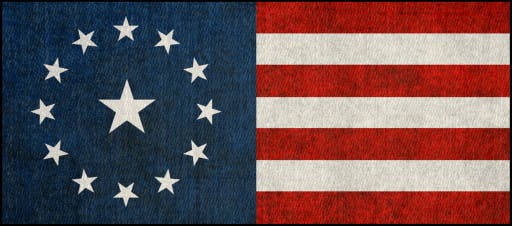

The sovereignty of states emerges from this same natural-law foundation. States existed before the federal government; they created it, delegated limited powers to it, and retained all remaining authority. This structure—known as state sovereignty—is encoded in the Tenth Amendment, which declares that all powers not granted to the federal government remain with the states or the people. This amendment is not decorative; it is the backbone of American federalism. It ensures that the federal government cannot intrude into matters of education, healthcare, property law, policing, commerce, or any domain not explicitly assigned to it. The states act as regional guardians of liberty, standing between the people and federal overreach.

The relationship between the states and the federal government is known as the compact theory. Under this doctrine, the Constitution is understood as a contract among sovereign states. States voluntarily joined the Union, and in doing so, delegated specific enumerated powers to the federal government. This delegation did not extinguish state sovereignty—it formalized it. Each state remains a sovereign entity with its own constitution, legislature, courts, and executive authority. This structure allows for diversity, experimentation, and regional autonomy, preventing the entire nation from collapsing under uniform error or centralized tyranny.

The compact theory also reveals a profound truth: the federal government does not own the states. It does not create them, dominate them, or outrank them. Instead, the states collectively own the federal government—creating it, defining it, limiting it, and retaining the lawful authority to restrain it. This inversion of traditional political architecture—where regional entities hold higher sovereignty than the central government—makes the united States of America unique among nations. It reflects the Founders’ understanding that concentrated power is the enemy of liberty, and that the only safeguard against tyranny is a decentralized structure rooted in the sovereignty of the individual and reinforced through sovereign states.

But sovereignty is not merely a legal construction; it is a responsibility. A sovereign individual must think, speak, act, and govern themselves with maturity and clarity. Sovereignty is not a license for chaos or rebellion; it is a call to moral discipline and self-governance. The Founders did not assume that liberty would be preserved through laws alone—they placed equal weight on virtue, education, and civic engagement. A free people cannot remain free if they are unwilling to govern themselves, defend their rights, participate in their communities, and hold their governments accountable.

At the same time, sovereignty is not something that governments grant or revoke—it is something individuals either remember or forget. A population unaware of its sovereignty becomes easy prey for corporate, bureaucratic, or political entities seeking control. This is where the distinction between constitutional authority and corporate authority becomes crucial.

Constitutional authority arises from the people and is exercised through limited government structures. It is bound by natural law, restrained by the Constitution, and accountable through elections, juries, and public participation. It requires transparency, consent, and lawful justification for every action. Corporate authority, however, arises from charters, contracts, administrative codes, and commercial regulations. It operates through agencies, policies, and enforcement mechanisms that are often insulated from public oversight. Corporate authority can be used lawfully—but it can also be used to bypass constitutional limitations.

Over time, the rise of administrative agencies, corporate-government partnerships, and statutory frameworks has blurred the line between constitutional governance and corporate control. Regulatory bodies now issue rules with the force of law; private institutions influence public policy; financial entities shape national priorities. This evolution has allowed corporate authority to overshadow constitutional authority in certain domains—creating a system where the individual is treated less as a sovereign and more as a managed resource within an administrative grid.

The Founders anticipated this danger. They warned against entanglement with banking institutions, foreign influence, standing armies, and centralized power. They understood that sovereignty must be defended not just from external enemies but from internal drift. The Constitution therefore includes numerous mechanisms—jury trials, state legislatures, the militia principle, free speech protections, and strict limits on federal power—to ensure that the people retain their sovereign status.

Yet sovereignty is ultimately a vibrational state—a frequency of awareness and alignment. A sovereign individual understands the source of their rights, the limits of government, and the responsibilities of freedom. A sovereign state understands its role as a guardian of the people and a barrier against federal expansion. A sovereign nation understands that liberty is maintained through vigilance, unity, and principled governance.

When individuals awaken to this truth, the entire Republic strengthens. When individuals forget it, the Republic weakens. Sovereignty is therefore not merely a legal condition—it is a living field of consciousness that must be cultivated, protected, and activated.

The sovereignty of the individual and the state, acting in harmony, forms the twin pillars of the American project. Without the individual, there is no source of authority. Without the states, there is no shield against centralization. Without the Constitution, there is no lawful structure to bind the whole system together.

In this harmony lies the genius of the Founders’ design. They built a Republic where the smallest unit—the individual—is the sovereign seed, and the largest unit—the federal government—is the servant. This inversion of traditional power structures is what makes America not just a nation, but an idea: the idea that human beings can govern themselves, live free under natural law, and preserve a society built on dignity, virtue, and responsibility.

As America moves into a new era, the rediscovery of sovereignty—individual and state-level—will be essential. Only when the people reclaim their role as the ultimate authority can the Republic restore its original balance. Only when the states assert their constitutional standing can the system realign with its foundational blueprint. And only when individuals embody the frequency of sovereignty can the united States of America rise into its next evolution as a nation rooted in liberty, driven by truth, and aligned with natural law.